Sunday, December 13, 2009

Jafar Panahi

Jafar Panahi was ten years old when he wrote his first book, which subsequently won the first prize in a literary competition. At the same age, he became familiar with film making. He shot films on 8mm film, acting in one and assisting in the making of another. Later, he took up photography. During his military service, Panahi served in the Iran–Iraq War (1980-90) and made a documentary about the war during this period.

After studying film directing at the College of Cinema and Television in Tehran,[2] Panahi made several films for Iranian television and was the assistant director of Abbas Kiarostami's film Through the Olive Trees (1994). Since that time, he has directed several films and won numerous awards in international film festivals.

Panahi's first feature film came in 1995, entitled White Balloon. This film won a Camera d'Or at the Cannes Film Festival. His second feature film, The Mirror, received the Golden Leopard Award at the Locarno Film Festival.

His most notable offering to date has been The Circle (2000), which criticized the treatment of women under Iran's Islamist regime. Jafar Panahi won the Golden Lion, the top prize at the Venice Film Festival for The Circle, which was named FIPRESCI’s Film of the Year, and appeared on Top 10 lists of critics worldwide.[3]. Panahi also directed Crimson Gold in 2003, which brought him the Un Certain Regard Jury Award at the Cannes Film Festival. It went on to win a number of best film awards and received excellent critical acclaims.[citation needed]

Panahi winning the Berlin Silver Bear award for his achievement in film in 2006

Panahi's Offside (the story of girls who disguise themselves as boys to be able to watch a football match) was nominated for competition in the 2006 Berlin Film Festival, where he was awarded with the prestigious Silver Bear and the Jury Grand Prix, 2006.

On July 30, 2009, Mojtaba Samienejad, an Iranian blogger and human rights activist writing from inside Iran, reports Panahi was arrested on Thursday at the cemetery in Tehran where mourners had gathered near the grave of Neda Agha-Soltan.

Panahi's style is often described as an Iranian form of neorealism.[citation needed] Jake Wilson describes his films as connected by a "tension between documentary immediacy and a set of strictly defined formal parameters" in addition to "overtly expressed anger at the restrictions that Iranian society imposes".[5] His film Offside is so ensconced in the reality that it was actually filmed in part during the event it dramatizes – the Iran-Bahrain qualifying match for the 2006 World Cup.

Where Panahi differs from his fellow realist filmmaker Abbas Kiarostami, is in the explicitness of his social critique. Stephen Teo writes that

"Panahi's films redefine the humanitarian themes of contemporary Iranian cinema, firstly, by treating the problems of women in modern Iran, and secondly, by depicting human characters as "non-specific persons" - more like figures who nevertheless remain full-blooded characters, holding on to the viewer's attention and gripping the senses. Like the best Iranian directors who have won acclaim on the world stage, Panahi evokes humanitarianism in an unsentimental, realistic fashion, without necessarily overriding political and social messages. In essence, this has come to define the particular aesthetic of Iranian cinema. So powerful is this sensibility that we seem to have no other mode of looking at Iranian cinema other than to equate it with a universal concept of humanitarianism."

Panahi says that his style can be described as "humanitarian events interpreted in a poetic and artistic way". He says "In a world where films are made with millions of dollars, we made a film about a little girl who wants to buy a fish for less than a dollar (in The White Balloon) - this is what we're trying to show."

In an interview with Anthony Kaufman, Panahi said: "I was very conscious of not trying to play with people's emotions; we were not trying to create tear-jerking scenes. So it engages people's intellectual side. But this is with assistance from the emotional aspect and a combination of the two."

filmography

* The Wounded Heads (Yarali Bashlar, 1988)

* Kish (1991)

* The Friend (Doust, 1992)

* The Last Exam (Akharin Emtehan, 1992)

* The White Balloon (Badkonake Sefid, 1995)

* Ardekoul (1997)

* The Mirror (Ayneh, 1997)

* The Circle (Dayereh, 2000)

* Crimson Gold (Talaye Sorkh, 2003)

* Offside (2006)

Awards and honors

Jafar Panahi has won numerous awards up to now. Here are a few representatives:

* HIVOS Cinema Unlimited Award (2007)

* Podo Award, at Valdivia Film Festival (2007), for his life-time artistic accomplishments.

* Silver Bear, Berlin Film Festival, 2006.

* Prix du Jury - Un Certain Regard, Cannes Film Festival, 2003.[7]

* Golden Lion, Venice Film Festival, 2000.

* Golden Leopard, Locarno International Film Festival, 1997.

* Prix de la Camera d'Or, Cannes Film Festival, 1995.

Iranian Filmmaker Jafar Panahi Arrested In Tehran

by Peter Knegt (July 30, 2009)

Iranian Filmmaker Jafar Panahi Arrested In Tehran

Jafar Panahi at the 2006 Toronto International Film Festival, where his film "Offside" was screening. Photo by Brian Brooks/indieWIRE.

AFP is reporting that prominent Iranian director Jafar Panahi (“Offside”, “The Circle”) was arrested today, along with his wife and daughter, at a ceremony where mourners gathered to commemorate slain election protesters. AFP notes that “Panahi is a vocal critic of Iran hardliners and his movies have been banned for a decade from domestic cinemas despite their international success.” Several other mourners were also arrested by Iranian riot police. They were marking the 40th day since the death of Neda Agha-Soltan, a woman “who came to symbolise the protest movement against the re-election of President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad.”

The Times Online is also covering the events, while The New York Times is running a constantly updated blog on the protests, including information about Panahi.

Jafar Panahi, born in 1960 in Mianeh, Iran, was ten years old when he wrote his first book, which subsequently won first prize in a literary competition. It was also at that young age that he became familiar with filmmaking: shooting films on 8mm, acting in one 8mm film and assisting in the making of another. Later, he took up photography. On being drafted into the military, Panahi served in the Iran-Iraq War (1980-90), and during this period, made a documentary about the War which was eventually shown on TV. After his military service, Panahi entered university to study filmmaking, and while there, made some documentaries. He also worked as an assistant director on some feature films. After his studies, Panahi left Tehran to make films in the outer regions of the country. On returning to Tehran, he worked with Abbas Kiarostami as his assistant director on Through the Olive Trees (1994). Armed with a script by his mentor, Kiarostami, Panahi made his debut as a director with The White Balloon (1995), and subsequently went on to make The Mirror (1997) and his most recent film, The Circle (2000).

On the surface, Panahi's films offer a variation of neo-realism, Iranian-style, by capturing, in his own words, the "humanitarian aspects of things". But watching the director's latest film The Circle (currently doing its rounds on the international film festival circuit after winning the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival last year), one can't help but feel that his humanitarian cinema is a cloak, masking an even greater obsession. His motif of the circle - the camera beginning from a single point and revolving around characters only to return to the point where it began - aptly describes that obsession, expressed as much as possible through the form of the plan séquence (a long uninterrupted take). The circle is both a metaphor for life as well as a form that the director has subscribed to as his most representative style. Stressing the equal importance of both form and content, Panahi asserts that his work is about "humanity and its struggle", or the need for human beings to break through the confines of the circle.

In his own rather startling way, Panahi's films redefine the humanitarian themes of contemporary Iranian cinema, firstly, by treating the problems of women in modern Iran, and secondly, by depicting human characters as "non-specific persons" - more like figures who nevertheless remain full-blooded characters, holding on to the viewer's attention and gripping the senses. Like the best Iranian directors who have won acclaim on the world stage, Panahi evokes humanitarianism in an unsentimental, realistic fashion, without necessarily overriding political and social messages. In essence, this has come to define the particular aesthetic of Iranian cinema. So powerful is this sensibility that we seem to have no other mode of looking at Iranian cinema other than to equate it with a universal concept of humanitarianism.

The Circle works on the level of interpreting "humanitarian events in a poetic or artistic way," as the director himself defines his own version of neo-realist cinema. But the film is a far bolder work than most recent Iranian films; and one measure of its boldness is the fact that it is banned in Iran. It chronicles the stories of seven women, not all of whom are connected to each other, but whose fates are invariably interrelated through a circle of repression. The film works as a riveting, compelling testament about the lowly status of women in Iranian society, and about the subtle means with which Iran as a whole exercises its repression over the female sex. Panahi is, however, ambivalent about the political content of The Circle. In the following interview, it comes as no surprise that Panahi prefers to accentuate the human dignity of his characters - a human right that seems trivial in the context of Western society but one which is readily denied in unexpected circumstances and situations, as Panahi himself found out, to his cost. On his way to the Buenos Aires International Festival of Independent Cinema on 15 April, 2001, after having attended the Hong Kong International Film Festival, Panahi was arrested in JFK Airport, New York City, for not possessing a transit visa. Refusing to submit to a fingerprinting process (apparently required under U.S. law), the director was handcuffed and leg-chained after much protestations to US immigration officers over his bona fides, and finally led to a plane that took him back to Hong Kong. As far as is known, this incident was not reported in any major US newspaper (1), even though The Circle was being shown in the United States at the time (another irony: for that film, Panahi was awarded the "Freedom of Expression Award" by the US National Board of Review of Motion Pictures. His letter to the Board is published in this issue.

This interview with Jafar Panahi was conducted in Hong Kong on 11 April on the occasion of the 25th Hong Kong International Film Festival, which presented The Circle, among other new Iranian films. On being invited to the Festival, the director encountered problems in securing a visa from the Chinese embassy in Tehran to enter Hong Kong (a fact that he made known to his audience whilst introducing The Circle). He was granted a visa only upon the intervention of the Hong Kong Festival which made clear to the embassy that Panahi was an eminent film director and that his visit to the territory was purely a cultural one. Clearly, the case of Jafar Panahi illustrates a modern paradox: his nationality is no guarantee of decent, "humanitarian" treatment outside of Iran (the country being demonized by the international community, so to speak), even though Iranian cinema - with Panahi himself as one of its most distinguished exponents - is perhaps the most humanitarian in the world today.

Apparently, Panahi is very much focused on this paradox, taking every opportunity to decry the poor treatment (either perceived or real) that he has received when travelling out of Iran (in Hong Kong, he voiced his discontent with the Chinese embassy during interviews with the press; and similarly, the director has spoken out against his "inhuman" treatment by the US immigration authorities in JFK Airport). Through his films, Panahi expounds the humanity of all his characters, good or bad, expressing the fundamental need for decent, humanist behaviour on the part of all. An indication of his focus may be gleaned from the interview itself. For instance, I began the interview by asking Panahi to define the aesthetics of Iranian cinema as he saw it. Perhaps a bit put off by the more intellectual tone of my question, Panahi went on to say that the aesthetics of Iranian cinema was married to the realistic, the actual: "the humanitarian aspects of things." Although the interview was conducted with the help of an interpreter, I could sense Panahi's stalwart personality, his total conviction about "humanity and its struggle", and his pride over what he has achieved in Iranian cinema. The case of Jafar Panahi will not be closed for a long while yet.

*

Stephen Teo: I would like you to begin by talking about the aesthetics of Iranian cinema. What I am struck by in all the Iranian films we have seen is the fact that they are very close to being a kind of documentary reality of Iran. But on the other hand, they're very beautiful to look at, unlike most realist-based cinemas - beautiful in the sense that they're not rough, shot with hand-held cameras with no lights, such as the neo-realist style of Italian cinema after the war. Could you give a definition of the aesthetics of Iranian cinema? How does it differ from the neo-realist style, for example?

Jafar Panahi: The Iranian cinema treats social subjects. Because you're showing social problems, you want to be more realistic and give the actual.the real aesthetics of the situation. If the audience feels the same as what they see, then they would be more sympathetic. Because you're talking about the humanitarian aspects of things, it will touch your heart. We talk about small events or small things, but it's very deep and it's very wide - things that are happening in life. According to this mode, it has a poetic way and an artistic way. This may be one of the differences between Iranian movies and the movies of other countries: humanitarian events interpreted in a poetic and artistic way. In a world where films are made with millions of dollars, we made a film about a little girl who wants to buy a fish for less than a dollar (in The White Balloon) - this is what we're trying to show.

Whatever shows the truth of the society, in a very artistic way - that will find its own neo-realism. But this depends on the period. In Italy, neo-realism was defined by its time after the war. And now in Iran, that kind of neo-realism is disappearing.

ST: I would like to ask about your use of the idea of the circle, in The Circle and also in The White Balloon. As in The Circle, The White Balloon also uses the motif of the circle. We watch in the beginning something happen and then it's like drawing a circle, it connects with a character, an event and then it comes back to the circle. So what is it about this use of the circle that appeals to you?

JP: In the first plan-séquence in The White Balloon, the camera starts from those people who're playing the tambourines as they enter a shop. Somebody comes out of the shop and the camera follows him and then there's a jeep and the camera follows the jeep. The camera then arrives at a woman who goes to a balloon seller. If you have followed anyone of these people, you would have arrived at the same point. It is like a wall within which they are living together, and their lives are intertwined. That little girl is like an excuse, that all these lives can be touched. But these are the lives of children. Through the eyes of children, it's a much nicer world that they see, because children are in a world where they are not really aware of the difficulties of adults. They're trying to achieve their ideals. But in the life of adults, like in The Circle, the characters come out of idealism and they're more realistic - they are the same children but now they have grown up and they see the world with realistic eyes.

All three films, The White Balloon, The Mirror and The Circle, are like full cycles - or circles - where the characters are facing up to problems, and they are trying to get out of their boundaries. In The Circle, we're specifically talking about, addressing, these cycles. The form also has become like a circle. We start from an opening and we go back to the same point. We start from a birth and we go through darkness . in this movie we start from one birth, the birth of a human being, and we go back again to this same point. I had the idea of this form from a racetrack, like running a 400m relay. The runners come back to the first point. If they win they win together, if they lose they lose together. But in reality it's the victory of one person.

Coming back to your first question: why is Iranian film so beautiful? When you want to say something like this and then you add an artistic form to it, you can see the circle in everything. Now our girl has become an idealistic person and thinks that she can reach for what she wants, so we open up a wide angle and we see the world through her eyes, wider, we carry the camera with the hand and we are moving just like her. When we get to the other person, the camera lens closes, the light becomes darker and it becomes slower. Then we reach the last person, there's no other movement; it's just still. If there's any movement, it's in the background. This way, the form and whatever you are saying becomes one: a circle both in the form and in the content.

ST: So the form of the circle is both a metaphor for life as well as your own style of filmmaking?

JP: Yes.

ST: When you have this circle, there's a lot of repetition. You watch the characters doing the same thing every time. And this is something that appears not only in your films but also in many other Iranian films that I've seen, for example in Kiarostami's films: he always repeats and repeats.

JP: Normally, an artist has one thing to say, and this is being expressed in different ways. But you don't see this as all being in the same shape. I'm making films about humanity and its struggle. This human being is trying to open up the circle that he encounters. Once when he is a child, and sometimes as an older person. This is what is being said in The White Balloon, that is, the understanding of a child. There might be ten other movies like that: they all have the same theme but you will enjoy each of them in a different way. In literature, there is also the same thing - for example, Garcia Marquez of 100 Years of Solitude. He's always talking about the same subject but in a different way. All artists are the same: we talk about one subject but in different ways. This is not repetition. This is the way they express it.how they see the world.

ST: I take your point, particularly when I'm watching your films. I see characters reacting, showing different emotions; so although there is repetition within the circle, I see that the characters, their emotions and gestures are different. Are you more concerned with human behaviour or are you more concerned with the narrative?

JP: We must contain all. It's what we accept from this that is important. It's both of these that make an identity. Two different things: the things that are said and the things that are acted are two different things. Sometimes they're similar. This is how you understand the personality of the person. You have to focus on both of these so that you get the character.

ST: In The Circle, which character do you identify with most?

JP: I like all of them in different ways, that's why I created them. The first girl who is young and very idealistic. It's what comes out of her age. Or the last person who has come to the end of her life and has accepted the conditions of her life. All of them are very important. But I myself don't like to think of a person accepting his or her conditions in life. I prefer that even in a closed circle, they still try to break out of that circle. But I accept that I have to be realistic. I have to accept that in a society there are people who accept their conditions.

ST: The subject matter of The Circle is controversial. You mentioned that the film is still banned in Iran. In fact when I was watching the film, I realized that through the characters, there's a lot of fear about the system, the establishment, the police. The women can't smoke; they have to wear the Chador; they seem to want to hide every time. This is all very clear from watching the film. Did you deliberately want to make a statement about the political situation in Iran?

JP: I have to tell you again that I'm not a political person. I don't like political movies. But I take every opportunity to comment on the social issues. I talk about the current issues. To me it's not important what is the reason for what has happened. Whether it's political reasons or geographical reasons: these are not important - but the condition, the social issues. It is important to me to talk about the plight of humanity at that time. I don't want to give a political view, or start a political war. I think that the artist should rise above this. Political movies have limited time. After that time, it doesn't say anything anymore. But if the whole thing is said in an artistic way, then it doesn't have a time limit. So it doesn't really serve a political purpose. Then it can be everlasting, for always, and it could be for anywhere. But I know that politically, with the film authorities, with any kind of film that has some political background in it, they would disagree with. And for this reason, that is what the problem is.

ST: Still, your film makes a very strong statement about the problems that women face in Iran.

JP: Yes, I agree with that.

ST: So that is humanitarian of course, but it's also political.

JP: Yes, I agree with that. It has the elements. It all depends on how you look at it. If a person has only political views, then he will only see the political. But if you are a poet or an artist, then you see other things as well in the movie. If you are a socialist, you see political or economical or whatever different points of view. You mustn't look at a film with only one point of view. If you want to see The Circle as political, then it is one of the most political movies in Iran. By political, I mean partisan politics. But even the police, I didn't want to show them as bad. In the first instance, you are afraid of the police. Because you are looking at them from the point of view of someone who is now in prison. And normally you see him in a long shot, but when they come nearer and you see them in a medium shot, you can see their human faces. Then it comes down to "Do you need any help". But he goes back again and becomes frightening. If I were being political, then I would always show the police as dangerous or bad persons.

ST: In a long shot.

JP: In a long shot.I would show them rough. A political person can only see black or white. But I intertwine the tones. This is where the humanitarian eye comes in. I don't want to bring somebody down or say, "Death to this, or life to that."

ST: I've seen The White Balloon and The Circle: they're both films about women. Obviously you feel a lot about the problems of women.

The Mirror

The Mirror

JP: I don't really know - but probably it was due to the fact that my first film was made with a very low budget, and I thought it would be easier to work with children. I thought that filming with children would meet with fewer problems with the censors. Perhaps too, at that time, I had my own children, and it went automatically down that road. I have both a boy and a girl and I can see that the girl can strike up relationships in an easier, milder way. So I thought that a girl could give a better impression. Then when I finished the film and I started The Mirror, I began to think about what happens now that the girl has grown up in society. And then automatically, it became a movie about women. It started unconsciously but now the question is settled.

ST: So now you have made a trilogy about women. They are all linked.

JP: I agree.

ST: Shall we talk a bit about the process of making your film? You use both amateurs and professionals?

JP: I haven't really tried to be either this way or that way. I just choose. I just try to see what roles I have and who they would fit. I look for the person who fits what is in my mind. I know that to bring the professional and amateur together is very difficult. The acting must be on the same level. At this point, normally it is more difficult for the professional, because the professional has to come down and adapt to the level of the amateurs. The amateur is not role playing but doing what comes naturally. So the professional has not to give a performance, but to learn how to be more natural.

ST: So how long did it take to make your film?

JP: 53 days from beginning to end. In the middle, there were about 18 days when we didn't work, either because the weather wasn't good or .There were 37 days of filming.

ST: Were there a lot of rehearsals?

JP: The first plan-séquence was repeated 13 times.the shot from the hospital to the street. The cameraman would film the scene and take the shot back to the laboratory to check it and then he would re-shoot it again. This was repeated 13 times until we got what we wanted. This is one of the difficulties of doing long sequences like this. If I had wanted to break it down, I could have done it in half a day. That sequence took about five days. There were seven to eight such long takes in the film.

ST: Who conceived the script?

JP: Myself. Took about a year. Then, I wrote the different characters - where they come from and where they go to, which took about two months.

ST: Was it based on a story or a novel?

JP: Original script.

ST: And all your films are original scripts?

JP: Yes.

ST: That's very remarkable. What about the photography? Do you handle the camera?

JP: I have a camera operator. But I do the editing.

ST: There are many elements in the film that remind me of folk culture. Like the end scene, where the prostitute is in the prison van and there's a fellow prisoner, a man who starts to sing, reminiscent of folk music or folk culture. And also in The White Balloon where the girl comes out in the street and there's the snake charmer. Do you consciously want to show all these elements?

JP: When you see the film with subtitles, you don't understand the original language. If you could understand, you would know that everyone has a different accent, like a folk song or folk dance from a different part of Iran. These accents and these tones of folk culture also help to make the film more attractive. Tehran is a very big city and there are people from all over Iran living in the city. This is one of the features of a big city. The people in the film help one another so that they are believable and true, and sometimes I do this purposely - like the three girls who were playing their guitars - they're speaking in the Azerbaijani language, and the young girl who is one of the three women in the beginning, also has an Azerbaijani accent. And when she's sitting in front of the painting, and talking about the countryside that she sees in the painting, she's actually talking about Azerbaijan. So there are all kinds of connections. That painting was something from Van Gogh, for example. I chose it because it was not a specific geographic place.it could be anywhere in the world, but it was inspired by an actual painting by Van Gogh. I wanted to say that where you want to be could be anywhere in the world.

ST: I want to ask about the three female characters in the beginning. I'm not sure what exactly they went to prison for.

JP: It doesn't matter. It could be anything you want. That's not important. It's a very delicate point. If I had decided to give them some crime that they were guilty of, like something political or because of drugs, they would become specific persons. But they are not specific persons. You can have anybody there. Then the problem is a much larger problem. Maybe if it were a specific person there would be no censorship. But when it's open to interpretation, then it's more difficult. If it was a specific person, the censors can then say this person has this kind of crime, then it's not a problem. Because I wanted the audience to think for themselves, I left it open to interpretation.

ST: What is your next project?

JP: This was such a difficult film for me. We wanted very much to show this film. In the past six months from the start of the first showing, I've always been travelling. I've been to many different countries in Asia, Europe, America, Africa.long trips. I haven't had time to think about the next project.

ST: Having travelled all over the world now, do you think that being a filmmaker in Iran is much more difficult than in other countries?

JP: Every country has its own difficulties. In some countries, it's a budget problem. In other countries, it's political problems. And in some places, it's a lack of knowledge about the movie industry. In some places, there are tools but there are no people. In other places, there are people but no tools to make films with. There are problems everywhere, in different shapes.

ST: Just to focus on Iran. For example, what are the censorship problems that you face?

JP: There's censorship in Iran and China - both closed countries and closed societies.

ST: Is it much more difficult to want to make a film about women in Iran?

JP: It is a problem, but there are about sixty movies made every year in Iran, and ten or fifteen of them are about women. We have women directors, making movies about women. In a society governed by men, these problems do exist.

ST: Do you practise self-censorship?

JP: Never. Whatever I want to say, I try to say it. If I were my own censor, then I may not have any problems. At first they didn't allow me to make the movie. We took about ten months. In the end, they gave me permission to make the movie. They gave me a letter and in the letter they said that after the film was made, they would evaluate it to see whether it could be shown. I forgot about the letter. I thought that I would make the movie first and then I decide what to do about the situation. If I had paid attention to the letter, I would have to be my own censor and maybe then, I would have been able to show my film in Iran.

ST: Would you call your film a documentary or a drama?

JP: It's a drama that has become a documentary.

ST: Have you heard of the term "docu-drama"?

JP: I make my film, then you name it.

CRIMSON GOLD

PLOT:

For Hussein, a pizza delivery driver, the imbalance of the social system is thrown in his face wherever he turns. One day when his friend, Ali, shows him the contents of a lost purse, Hussein discovers a receipt of payment and cannot believe the large sum of money someone spent to purchase an expensive necklace. He knows that his pitiful salary will never be enough to afford such luxury. Hussein receives yet another blow when he and Ali are denied entry to an uptown jewelry store because of their appearance. His job allows him a full view of the contrast between rich and poor. He motorbikes every evening to neighborhoods he will never live in, for a closer look at what goes on behind closed doors. But one night, Hussein tastes the luxurious life, before his deep feelings of humiliation push him over the edge.

An interview with Jafar Panahi, director of Crimson Gold

By David Walsh

17 September 2003

Jafar Panahi, Iranian director of Crimson Gold, was interviewed at the Toronto film festival by David Walsh.

David Walsh: This is an Iranian film with an obvious international significance. In the US such tragedies happen everyday. Unfortunately, one almost becomes accustomed to them. What was it about this particular incident that caught your attention?

Jafar Panahi: It’s true that when you live in a society like ours things like that happen all the time, but there are certain times, certain moments, certain days, when you hear what happens, the pain hits you so hard, you think about it seriously. It’s like when you take the same route from home to work every day and one day you notice for the first time something that was always there. You focus on it. It causes you pain and you think you have to do something about it.

So as a filmmaker, when I heard what happened it struck me and I had to do something about it. We were going to [director Abbas] Kiarostami’s photographic exhibition. When he told me what happened, I could not stay at the exhibition any longer and I felt I had to do something. I can’t even remember what kind of emotional feeling I had that day.

The party scene in the movie [the police raid] happens all the time, and young people are always struggling with the problem and they get arrested, and their parents sign papers that they won’t do it again. Three weeks ago, something happened in Tehran...although it was a very sad thing, I felt pleased that I had exposed this in my movie. Three weeks ago, after a party, the police followed a boy and girl, and fired at them, and the boy was killed. As a social filmmaker, I respond to whatever is happening in our social life.

Although the people living in that society are totally used to what happened at the party, it is necessary to expose it and show it again as a real problem.

Because the Iranian government is based on religion, any relationship between boys and girls—if they’re not married, if they’re dancing together at a party—is a crime. So they have to do something about it. Sometimes they have the proper papers and they have permission to raid the house. And sometimes they wait outside for people to come out—they can also catch more people like that.

DW: Is the question of social inequality a subject that is discussed by filmmakers, journalists and politicians in Iran? It is a major fact of life in the US, but hardly anyone talks about it or makes films about it.

JP: Inequality exists in every country of the world. But a certain point can be reached...there is no middle class anymore, because of wrong political decisions or economical problems. And then the gap between poor and rich gets bigger, and that’s how it is right now. That causes violence and aggravation. And the various people who are struggling with this problem react differently. Hussein was not a thief; if he had been, he would have stolen from the rich man. He wanted to defend his humanity against humiliation. We don’t want to say whether it’s right or wrong. But we say that’s how it is.

DW: The film showed me many things about Iran for the first time. We have never seen such wealthy homes before. Was that deliberate, to show such wealth?

JP: Yes, and that’s the way it is because of the gap that’s getting bigger between rich and poor. And the characters in the movie don’t even compare to the really wealthy people in Iran.

DW: There is not simply the economic effect, but the psychological and emotional impact, and not only on the poor. Did you also want to speak about the consequences for those with money?

JP: I want to show people at every level of society, and I want to show their problems. I don’t want to say that people at one level of society are better or worse off. We have about 4 to 5 million Iranian people who live outside Iran; they left the country after the revolution. Most of them were children when they fled the country, and they don’t have any real knowledge about what’s happening in Iran now. But as they love their country, they always want to go back and try to live there. But when they come back, they can’t relate to people and they suffer. That’s why he invited Hussein in, so they could talk about the problems. And we feel as bad for the rich guy as we do for Hussein.

DW: Hussein seems terribly injured, both by war and the economic situation. Do you feel that many Iranians have been wounded in this fashion?

JP: There is a saying that we think insane people are more fortunate, because they don’t really see what’s happening around them. But if you really see what’s going on around you, it’s going to make you suffer deeply. And that’s Hussein’s situation; he hardly talks, but he sees much, and when he sees something, he really sees deeply into it. And he is ill, and he suffers both physically and emotionally.

DW: Yesterday at the public screening, you described yourself as independent filmmaker. That is often a misused term in North America. What do you mean by “independent”?

JP: Independent from any kind of dependency and coercion anywhere in the world. Independent from any belief I think is not right. Refusing self-censorship and believing any movie that I make is, in the end, exactly what I wanted to say. A lot of times, when you say you’re independent, it means economically, that you don’t get paid by other people. But where we are, independent means more like independence from politics. That’s why I don’t make political movies. Because if I were a political filmmaker, then I would have to work for political parties and I would have to go along with their beliefs of what’s wrong and what’s right. But what I say is that art is much higher than politics. Art looks like politics from a higher end. You never say what’s wrong or right. We just show the problems.

And its up to the audience to decide what’s wrong or right. A political movie becomes dated, but an independent artistic film never gets old and is always fresh. Although I’m making my movies in Iran as a geographical area, my voice is an international one. That’s what I mean by “independent.” Whenever I feel pain, I’m going to respond, because I’m not dependent on any party, and I don’t take orders, and I decide independently when I make my movies. I try to struggle with all the difficulties and make my movie. If I weren’t independent, I would say yes to anyone. But when I want to make a movie, I’ll do anything it takes. And that’s not what government officials like. And the pleasure is much greater.

DW: I congratulate you on your criticism of the situation in Iran and your refusal to come to New York because of US government policy. What is your attitude toward the invasion of Iraq?

JP: People in the Middle East aren’t really optimistic about America. And all the ordinary people think that everything America does is to suit itself. And to serve its own self-interest, the US government disregards international opinion and law. We were in a war with Saddam for eight years, and America was supporting him the whole time. Saddam bombarded us with chemical weapons. But suddenly, when America saw its own interests threatened by Saddam, then they attack. We saw this in Afghanistan. When they wanted to invade Afghanistan, we had to laugh because we knew they would never find bin Laden. There is always going to be a scapegoat that American can use.

Hussein (Hossain Emadeddin) is a guy pretty down on his luck. He's an ex-soldier who was somehow injured, and now delivers pizza. He has a hulking presence about him, and pretty taciturn. Jafar Panihi (The Circle, Ardekoul) uses Hussein to show the imbalance in Iranian society; how some people get ahead economically but others get left behind. It's a pretty moving tale, albeit a thin one. This divide is large enough to cause Hussein to hold up a jewelry store, as he does at the beginning of Crimson Gold. Panihi and screenwriter Abbas Kiarostami (The Deserted Station, Ten) then flash back to show the events leading up to Hussein's actions.

Like other films in Persian cinema, Panihi uses non-actors. This brings a sense of realism to the roles, since the viewer is watching ordinary people do ordinary things. The one drawback is that these people are not trained to come across as natural, so their delivery is sometimes clumsy. For Emadeddin, it is hard to tell what he is thinking, because Panihi gives him so few lines. He moves slowly and deliberately, and the only obvious emotion he shows is annoyance at the people around him. Hussein lives in a run down apartment, and the only time he glimpses the upper class is along his pizza delivery route. Each delivery brings a tantalizing glimpse into spacious, opulent apartments that he will never be able to afford.

He finds a receipt for an expensive necklace and goes to visit the jewelry store. The owner (Shahram Vaziri) doesn't even let him and his friend (Kamyar Sheisi) inside. He returns later, dressed in a suit looking for jewelry. After a quick conversation, the owner suggests he find some cheaper jewelry elsewhere. Although he looks relatively unfazed, it is clear that this bothers him. Hussein wants some sort of recognition from Vaziri. Recognition from one of these members of the upper class would be a sort of redemption for Hussein. It proves that he is somebody, that he exists.

Hussein later ends up in a magnificent apartment, where he can see close up just what he does not have. Is it fair that he fought for his country, only to return to toiling away for nothing, while a spoiled kid can get so much? The world is passing Hussein by, and the more he thinks about it the more it bothers him. Crimson Gold is also a nice look at a segment of Iranian society seldom glimpsed in film; the affluent, successful part. They shut their doors to their countrymen, creating an artificial divide between the classes. For Panihi, it's an interesting study. It doesn't quite go anywhere, but it is interesting nonetheless.

Thursday, October 22, 2009

Çağan Irmak

Çağan Irmak

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Çağan Irmak (born 4 April 1970 in İzmir, Turkey) is a Turkish film director, producer and screenwriter. He graduated in Radio-TV and Film Studies from the Ege University.

He managed to attract a wider audience in Turkey as a successful writer and director. He is mostly famous for the TV series Çemberimde Gül Oya and Asmalı Konak, and for the movies Mustafa Hakkında Herşey, Babam ve Oğlum and Issız Adam. The soundtracks of his movies are celebrated as well.

[edit] Filmography

Movies:

- Bana Şans Dile (2001)

- Mustafa Hakkında Herşey (2004)

- Babam ve Oğlum (2005)

- Ulak (2007)

- Issız Adam (2008)

- Karanlıktakiler (2009)

Short movies:

- Bana Old and Wise'ı Çal (1998)

TV series:

- Şaşıfelek Çıkmazı (2000)

- Asmalı Konak (2002)

- Çemberimde Gül Oya (2004)

- Kabuslar Evi (2006)

- Yol Arkadaşım (2008)

Monday, October 19, 2009

Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter... and Spring

Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter... and Spring (UK: Spring, Summer, Autumn, Winter... and Spring) is a 2003 South Korean film about a Buddhist monastery which floats on a lake in a pristine forest. The story is about the life of a Buddhist monk as he passes through the seasons of his life, from childhood to old age.

The movie was directed by Kim Ki-duk, and stars Su Oh-yeong, Kim Young-min, Seo Jae-kyung, and Kim Jong-ho. The director himself appears as the man in the last stage of life. The quiet, contemplative film marked a significant change from his previous works, which were often criticized for excessive violence and misogyny.

The film is divided into five segments (the five seasons of the title), each segment depicting a different stage in the life of a Buddhist monk (each segment is roughly ten to twenty years apart, and is physically in the middle of its titular season).

SYNOPSISSPRING

The wooden doors of a gated threshold open on a small monastery raft that floats upon the tranquil surface of a mountain pond. The hermitage's sole occupants are an Old Monk (OH Young-soo) and his boy protege Child Monk (KIM Jong-ho). While exploring the world in and around their secluded idyll, Child Monk indulges in the capricious cruelties of boyhood. After tying stones to a fish, a frog, and a snake, Child Monk awakens to find himself fettered by a large stone Old Monk has bound to him. The old man calmly instructs the boy to release the animals, promising him that if any of the creatures die "you'll carry the stone in your heart for the rest of your life."

SUMMER

The doors open again on Boy Monk now aged 17 (SEO Jae-kyung) who meets a woman (KIM Jung-young) making a pilgrimage with her spiritually ill daughter (HAYeo-jin). "When she finds peace in her soul," Old Monk reassures the mother, "her body will return to health." The girl awakens desire in Boy Monk and the sensual flirtation between the two of them culminates in passionate lovemaking on pond-side rocks. After a furtive but tender tryst in the abbey's rowboat, the lovers are discovered by Old Monk. The girl, now healed, is sent back to her mother. Forsaking his monastery home, the infatuated Boy Monk follows her.

FALL

Long absent from the monastery, Young Adult Monk (KIM Young-Min), now a thirty year old fugitive, returns to the abbey raft still consumed by a jealous rage that has compelled him to commit a violent crime. When Young Adult Monk attempts penitence as cruel as his misdeed, Old Monk punishes him. The Old Monk instructs Young Adult Monk to carve Pranjaparpamita (Buddhist) sutras into the hermitage's deck in order to find peace in his heart. Two policemen arrive at the abbey to arrest Young Adult Monk but thanks to Old Monk, they let Young Adult Monk continue carving the sutras. Young Adult Monk collapses from exhaustion and the two policemen finish decorating the sutras before taking Young Adult Monk into custody. Alone again, Old Monk prepares a ritual funereal pyre for himself.

WINTER

The doors open on the now frozen pond and abandoned monastery. The now mature Adult Monk (played by director KIM Ki-duk) returns to train himself for the penultimate season in his spiritual journey-cycle. A veiled woman arrives bearing an infant that she leaves in Adult Monk's care. In a pilgrimage of contrition, Adult Monk drags a millstone to the summit of a mountain overlooking the pond. As he gazes down on the pond that buoys the monastery and the mountainsides that gently hold the pond like cupped hands, Adult Monk acknowledges the unending cycle of seasons and the accompanying ebb and flow of life's joys and sorrows.

... AND SPRING

The doors open once again on a beautiful spring day. Grown from a child to a man and from a novice to a master, Adult Monk has been reborn as teacher for his new protege. Together, Adult Monk and his young pupil are to start the cycle anew...

ABOUT THE FILM

The exquisitely beautiful and very human drama SPRING, SUMMER, FALL, WINTER... AND SPRING, starring director KIM Ki-duk, is entirely set on and around a tree-lined lake where a tiny Buddhist monastery floats on a raft amidst a breath-taking landscape. The film is divided into five segments with each season representing a stage in a man's life. Under the vigilant eyes of Old Monk (wonderful veteran theatre actor OH Young-soo), Child Monk learns a hard lesson about the nature of sorrow when some of his childish games turn cruel.

In the intensity and lushness of summer, the monk, now a young man, experiences the power of lust, a desire that will ultimately lead him, as an adult, to dark deeds. With winter, strikingly set on the ice and snow-covered lake, the man atones for his past actions, and spring starts the cycle anew...

With an extraordinary attention to visual details, such as using a different animal (dog, rooster, cat, snake) as a motif for each section, writer/director/editor KIM Ki-duk has crafted a totally original yet universal story about the human spirit, moving from Innocence, through Love and Evil, to Enlightenment and finally Rebirth.

DIRECTOR'S STATEMENT

"I intended to portray the joy, anger, sorrow and pleasure of our lives through four seasons and through the life of a monk who lives in a temple on Jusan Pond surrounded only by nature." -- KIM Ki-duk

ABOUT THE SET

The hermitage that is the stage for SPRING, SUMMER, FALL, WINTER... AND SPRING is an artificially constructed set made to float on top of Jusan Pond in North Kyungsang Province in Korea. Created about 200 years ago, Jusan Pond is an artificial lake in which the surrounding mountains are reflected in its waters. It retains the mystical aura of having trees more than hundreds of years old still growing within its water. LJ Film was able to obtain permission to build the set after finally convincing the Ministry of Environment through six months of negotiations.

ABOUT THE DIRECTOR

A unique, visionary voice within both South Korea's ongoing filmmaking resurgence and contemporary world cinema, 43 year-old acclaimed director KIM Ki-duk is a virtual autodidact. "I have been accustomed to a life quite different from other filmmakers," he says. Indeed, without benefit of a formal film school education, Mr. KIM has beaten his own path to a position of rapidly growing filmmaking eminence at home and abroad. After a customarily brief rural primary school education, he worked in factories until called for military service. During a five-year stretch in the South Korean Army, Mr. KIM developed a committed passion for painting. Upon completion of his military service, Mr. KIM moved to France, studied fine arts in Paris and sold his paintings on the streets in the south of France.

"One day," he says, "I woke to discover the world of cinema, and jumped into it." After collecting awards and accolades for his screenplay, A Painter and A Criminal Condemned to Death, Mr. KIM made his directorial debut, Crocodile in 1996. Since then KIM Ki-duk has, at the impressive speed of one film a year, created a series of films characterized by both an unblinkingly perceptive view of human behavior and a powerfully lyrical visual imagination. His films also have reflected and addressed the intersection of Mr. KIM's varied life experience with many of the questions confronting modern South Korean and world society or, as he says, "the borderline where the painfully real and the hopefully imaginative meet."

1997's Wild Animals explores North and South Korean enmity and reconciliation through the volatile friendship of two Korean exiles living in Paris. Birdcage Inn (1999 Berlin International Film Festival, Panorama Selection) probes class schisms even on the very fringes of society. The Isle (2000 Venice Film Festival, 2000 Rotterdam Film Festival, 2000 Moscow Film Festival Jury Prize and winner of the Sundance Film Festival's World Cinema Award) is an intoxicating and challenging contemporary love story set in a near-mythic locale. Real Fiction (2001 Moscow Film Festival) is an ambitious real-time, multi-format experiment and Address Unknown (2001 Venice and Toronto Film Festivals) takes an unusually intimate and non-judgmental look at the fifty year US military presence in Mr. KIM's homeland.

KIM Ki-duk's newest film, SPRING, SUMMER, FALL, WINT... AND SPRING, is a potent visualization of the passions inhabiting the human spirit and the understanding and acceptance which form the very substance of our lives. Mr. KIM is currently working on his 10th feature, a revenge story entitled Samaria.

KIM KI DUK FILMOGRAPHY

THE COAST GUARD (2002)

2003 Karlovy Vary Film Festival

BAD GUY (2002)

2002 Berlin International Film Festival

2002 Helsinki International Film Festival

ADDRESS UNKNOWN (2001)

2002 Venice International Film Festival

2002 Toronto International Film Festival

REAL FICTION (2000)

2001 Moscow International Film Festival, Competition Selection

THE ISLE (1999)

2000 Sundance Film Festival, World Cinema Award

2000 Venice International Film Festival

2000 Moscow International Film Festival, Special Jury Prize

2000 Rotterdam International Film Festival

BIRDCAGE INN (1998)

1999 Berlin International Film Festival, Panorama Selection (Opening)

1999 Moscow International Film Festival, Special Panorama Selection

1999 Montreal World Film Festival

WILD ANIMALS (1997)

1998 Vancouver International Film Festival

CROCODILE (1996)

Pusan International Film Festival

Film Review

By Frederic and Mary Ann Brussat

Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter . . . and Spring

Directed by Kim Ki-duk

Columbia TriStar Home Entertainment 03/04 DVD/VHS Feature Film

R - some strong sexuality

Welcome to a small Buddhist monastery situated on a raft floating in the center of a mountain pond. An old monk (OH Young-soo) is trying to pass on his wisdom to a child monk (KIM Jong-ho). His teachings are connected to the four seasons, and they accrue over the years.

The student still has some rough edges. In "Spring," the first part of the film, the boy and the master go to gather herbs from the forest for use in their healing arts. Off on his own, the boy plays a game in which he ties stones to a fish, a frog, and a snake, laughing as his victims move away slowly with their new burdens. The next day, he wakes up to discover that the Old Monk has tied a large stone on his back. He is told that he must find and release the animals and if any of them is dead, "you'll carry the stone in your heart for the rest of your life." The lesson burns its way into the boy's consciousness.

In "Summer," the young monk (SEO Jae-kyung) is 17 and just getting interested in the outside world. He is quite excited when a woman (KIM Jung-young) arrives at the monastery with her sickly daughter (HAYeo-jin). After some time spent in prayer, the Old Monk tells the mother, "When she finds peace in her soul, her body will return to health." The young Monk's desire is aroused from contact with the girl, and they eventually have sex. The Old Monk does not chastise his protégé but warns him that lust awakens the need to possess, and this can lead to even greater troubles. But the young Monk cannot hear the words and after the girl is sent away healed, he follows after her taking a Buddha statue and his few possessions.

In "Fall," the Old Monk brings a large white cat to be his companion on the raft. The Young Adult Monk (KIM Young-Min) returns to the monastery as a fugitive from the law consumed by anger. To calm him down so that he can tap into the peace within, the Old Monk orders him to carve Buddhist sutras into the deck of the hermitage. Two policemen arrive to arrest the Young Adult Monk, but they allow him to finish his penance. When he collapses in exhaustion, they help decorate the sutras before taking him away. This is a beautiful scene and a rare one — a visual metaphor for the impact of sacred teachings upon a small community.

In "Winter," many years have passed, and the Old Monk has died. Ice covers the pond when the mature Adult Monk (KIM Ki-duk, also the director of the film) returns to pick up where he left off so many years ago in his training. To make sure that his mind and body are fit, he practices a martial art on the ice. A woman who has covered her face with a purple cloth arrives at the monastery with an infant. Then, after leaving her child behind, she falls through a hole in the ice and drowns.

The Adult Monk takes out a statue of Kwan Yin, the Goddess of Compassion, then attaches a millstone to his body with a rope and drags it the top of a mountain. With this act, he carries in his heart all the suffering he has endured as well as the suffering of those he has come in contact with. From a place overlooking the pond in the distance, he meditates on Kwan Yin. Then he returns to pick up the cycle of the seasons. In "Spring" again, he begins training the child to be a monk, even as he was trained in the wisdom of Buddhism and the healing arts

This sense luscious film written and directed by KIM Ki-duk is one of the best films of the year. It is a luminous meditation on the wisdom of Buddhism and the cycles of human life as they are played out in the pristine beauty of the natural world. The images of the monastery floating on a raft are perfect in that they enable us to see the transitory and impermanent qualities of the world we live in day by day. Using the four seasons as a backdrop for the spiritual teachings of compassion, suffering, loss, desire, attachment, and transformation works perfectly. We loved feasting our senses upon the 300-year-old tree, the ripples of the pond, the varied animals at the hermitage, the mist that shrouds the pond in mystery, the monks' daily devotional rituals, and the many excursions to shore where a gate opens to the wider world that lies beyond. Everyone who experiences this extraordinary film will savor the complex emotions that make life such an exquisite spiritual teacher.

Thursday, July 23, 2009

American Beauty

Lester Burnham (Spacey) is a 42-year-old writer who despises his superiors and feels his job has few prospects for advancement. His wife, Carolyn (Bening), is an ambitious real-estate broker; their 16-year-old daughter, Jane (Birch), abhors her parents, has low self-esteem and is saving money for a breast augmentation operation. The Burnhams' new neighbors are United States Marine Corps Colonel Frank Fitts (Cooper), his dissociative wife, Barbara (Janney), and their teenage son, Ricky (Bentley).

After watching a high school basketball game at which Jane is a cheerleader, Lester develops an infatuation with Jane's sexually precocious friend and classmate, Angela Hayes (Suvari). His fantasies entail a sexually aggressive Angela among red rose petals.

Frank controls Ricky with a strict disciplinarian lifestyle and gives him regular drug tests. Ricky, an avid pot smoker and drug dealer, makes deals with a client of his so he can have clean urine samples to get around these tests. Upon meeting a homosexual couple in the neighborhood, Frank reacts with disgust. Ricky frequently uses a hand-held video camera to record his surroundings and keeps hundreds of tapes in his bedroom.

Carolyn begins an affair with her business rival, Buddy Kane (Gallagher). Lester is about to be laid off when he blackmails his boss, quits his job and takes up low-pressure employment at a fast food chain. He trades in his car for a 1970 Pontiac Firebird, starts running, and lifts weights so he can "look good naked" to impress Angela, who he overheard telling Jane that she would find him sexy if he had more muscle. He takes up smoking marijuana, which he buys from Ricky. Lester continues to fantasize about Angela and flirts with her whenever she visits Jane, to the latter's disgust. Jane's friendship with Angela wanes and Jane begins a romantic relationship with Ricky; the two bond over his camcorder footage of what Ricky considers the most beautiful imagery he has filmed: a plastic bag that is being blown by the wind in front of a wall. Later that night, after a tense dinner and being slapped by her mother (who feels Jane is ungrateful for all she has), Jane reveals herself to Ricky through the window as he films her.

Lester accidentally discovers Carolyn's infidelity, but reacts indifferently. Buddy responds by breaking off the affair with the excuse that it could lead to a financially ruinous divorce for him. Frank becomes suspicious of Lester and Ricky's friendship and searches his son's room. He finds camcorder footage of Lester lifting weights in his garage while nude; Ricky had captured the footage by chance. After watching Ricky and Lester's drug rendezvous through the garage window, Frank mistakenly concludes that the two are engaged in a sexual relationship. That evening, Ricky returns home, where Frank beats him and accuses him of being a homosexual. Ricky falsely admits the charge and goads Frank into turning him out of their home. Ricky goes to Jane and asks her to flee with him to New York City. Angela protests and Ricky answers her vanity about her appearance by calling her ordinary.

Carolyn loads a gun and drives home. Frank confronts Lester in the garage and attempts to kiss him; Lester rebuffs the advance and Frank flees home. Moments later, Lester finds a distraught Angela; she asks him to confirm her beauty, and when Lester responds affirmatively, she begins to seduce him. After learning Angela is a virgin, Lester withdraws, and they bond instead over their shared personal frustrations. Angela tells Lester that Jane is in love; Lester answers Angela's question to his wellbeing by telling her he is happy. Angela goes to the bathroom and Lester smiles at a family photograph in the kitchen. A gunshot rings out and blood spatters on the kitchen wall in front of Lester as he is shot from behind. Ricky and Jane find him dead. Lester's final narration reflects on his life, and the actions of the other characters at the moment of his death are shown intermittently: Frank's returning home, bloodied, a gun missing from his collection, showing who the killer of Lester was; Carolyn's crying in their bedroom. Despite his death, Lester says he is happy, explaining that it is hard to be mad when there is so much beauty in the world.

Title Song

The track song Hua Yang De Nian Hua is based on a song by famous singer Zhou Xuan from the Solitary Island period. The 1946 song, used in Wong's film, is a peaen to a happy past and an oblique metaphor for the darkness of Japanese-Occupied Shanghai. Wong also set the song to his 2000 short film, named Hua Yang De Nian Hua after the track.

- 花樣的年華 The years slipped past like flowers...

- 月樣的精神 the vigorous light of the moon

- 冰雪樣的聰明 bright, clever as glacier snow

- 美麗的生活 our beautiful life

- 多情的眷屬 my affectionate spouse

- 圓滿的家庭 this happy and fulfilled family...

- 驀地里這孤島籠罩著慘霧愁云 suddenly gloomy clouds and fog loom across this solitary isle

- 慘霧愁云 clouds of gloom and melancholy

- 啊,可愛的祖國 Ah, my lovely Motherland

- 几時我能夠投進你的怀抱 when can I go back into your arms

- 能見那霧消云散 and see these fogs dispel

- 重見你放出光明 and behold you give off light again

- 花樣的年華 as in those flower-like years

- 月樣的精神 and of the moon...

Wednesday, July 22, 2009

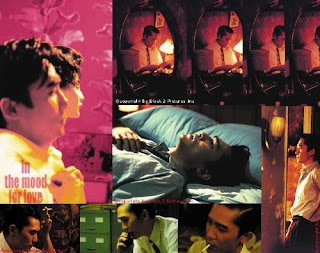

In the mood

In the Mood is a stylistic masterpiece for so many reasons, the most obvious being the sheer beauty of it. Wong Kar-Wai's camera immortalizes everything in frame, from cigarette smoke to droplets of rain, from noodle steam to the grill of a small metal fan. And unlike the oppressive floating bag speech in American Beauty, In the Mood just shows you the damn beauty without the instructions. And what about that dress she had on during the umbrella scene? Hey now. And the narrow red hallway in that hotel. So Il Notte in Shining color. And the music? It proved once and for all that you don't need Yo-Yo Ma to have a good cello soundtrack. Now you could argue there's just too much beauty, too much music and slow motion,

In the mood for love

It is a restless moment.

She has kept her head lowered,

to give him a chance to come closer.

But he could not, for lack of courage.

She turns and walks away.

That era has passed.

Nothing that belonged to it exists any more.

He remembers those vanished years.

As though looking through a dusty window pane,

the past is something he could see, but not touch.

And everything he sees is blurred and indistinct.

Plot

The movie takes place in Hong Kong, 1962. Chow Mo-Wan (Tony Leung), a journalist, rents a room in an apartment of a building of a Shanghaiese family, on the same day as So Lai-zhen (Maggie Cheung), a secretary from a shipping company. They become next-door neighbours. Each has a spouse who is working and often leaves them alone on overtime shift. Despite the presence of a friendly landlady, Mrs Suen, and bustling, mahjong-playing neighbours, Chow and So often find themselves alone in their rooms, and they begin to strike up a friendship.

Chow and So finally admit their shared suspicions that their spouses are cheating on them with each other. Chow persuades So to re-enact what they imagine might have happened between their partners' and their lovers, and slowly the line between play-acting and real romance blurs.

Chow invites So to help him and write a martial arts series story that he has longed to create for ages. As their relationship draws closer, people begin to notice and suspect they are in love. Meanwhile Chow and So are convinced that they are no more than friends and will not end up like their spouses. However, as time passes, Chow falls in love with So. Firm in his moral convictions that forbid adultery, he leaves Hong Kong for a job offered by his old friend in Singapore. Chow asks So to leave with him, but she turns him down and Chow then leaves on his own. But not before they spend one night together.

The next year, So goes off to Singapore and visits Chow's apartment there. She calls Chow, who is working for a Singaporean newspaper. Yet, when Chow picks up, So remains silent... Later, Chow realises she has visited his apartment after seeing a lipstick-stained cigarette butt left on his ashtray.

Three years later, So goes back to her old landlord, Mrs. Suen's apartment and pays her a visit. Knowing that she is about to emigrate to the USA, she asks to rent her property again, but this time the entire apartment. Later on, Chow also comes back, presumably only for a visit as well. He finds out that his old landlord, Mr. Koo, has emigrated to the Philippines. The man living in the room tells him that a woman and her son are living next door, and Chow smiles. On his way out, he pauses briefly at his old neighbor's door before leaving.

The setting of the final narration of the story is at Phnom Penh, Cambodia, Chow is seen visiting the Angkor Wat and whispers several years worth of secrets into a hole in a wall, before plugging the hole with mud - a method that he mentions by which a secret can be kept whilst dining with his old friend during his stay in Singapore.

Saturday, June 27, 2009

Pursuit of Happyness- Memorable quotes

Christopher Gardner: You gotta trust me, all right?

Christopher: I trust you.

Christopher Gardner: 'Cause I'm getting a better job

Christopher Gardner: I met my father for the first time when I was 28 years old. I made up my mind that when I had children, my children were going to know who their father was.

Christopher Gardner: Hey. Don't ever let somebody tell you... You can't do something. Not even me. All right?

Christopher: All right.

Christopher Gardner: You got a dream... You gotta protect it. People can't do somethin' themselves, they wanna tell you you can't do it. If you want somethin', go get it. Period.

Christopher Gardner: There's no salary?

Jay Twistle: No.

Christopher Gardner: I was not aware of that. My circumstances have changed some.

Martin Frohm: What would you say if man walked in here with no shirt, and I hired him? What would you say?

Christopher Gardner: He must have had on some really nice pants.

Christopher Gardner: [about the spelling mistakes in the graffiti of a building] It's not H-A-P-P-Y-N-E-S-S Happiness is spelled with an "I" instead of a "Y"

Christopher: Oh, okay. Is "Fuck" spelled right?

Christopher Gardner: Um, yes. "Fuck" is spelled right but you shouldn't use that word.

Christopher: Why? What's it mean?

Christopher Gardner: It's, um, an adult word used to express anger and, uh, other things. But it's an adult word. It's spelled right, but don't use it.

Christopher Gardner: Probably means there's a good chance. Possibly means we might or we might not.

Christopher: Okay.

Christopher Gardner: So, what does probably mean?

Christopher: It means we have a good chance.

Christopher Gardner: And what does possibly mean?

Christopher: I know what it means! It means we're not going to the game.

Christopher Gardner: It was right then that I started thinking about Thomas Jefferson on the Declaration of Independence and the part about our right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. And I remember thinking how did he know to put the pursuit part in there? That maybe happiness is something that we can only pursue and maybe we can actually never have it. No matter what. How did he know that?

[repeated line]

Christopher: Where are we going?

Christopher: Hey dad, you wanna hear something funny? There was a man who was drowning, and a boat came, and the man on the boat said "Do you need help?" and the man said "God will save me". Then another boat came and he tried to help him, but he said "God will save me", then he drowned and went to Heaven. Then the man told God, "God, why didn't you save me?" and God said "I sent you two boats, you dummy!"

[last lines]

Christopher Gardner: How many planets are there?

Christopher: Um... 7?

Christopher Gardner: Seven? Nine! OK, who's the king of the jungle?

Christopher: The gorilla?

Christopher Gardner: Gorilla? Nope. Lion.

Christopher: Yeah, lion, lion. You wanna hear something funny?

Christopher Gardner: OK.

Christopher: Knock knock.

Christopher Gardner: Who's there?

Christopher: Shelby.

Christopher Gardner: Shelby who?

Christopher: Shelby comin' round the mountain when she comes, Shelby comin' round the mountain when she comes!

Christopher Gardner: Hey, that's good.

Christopher: Knock knock.

Christopher Gardner: Who's there?

Christopher: Nobody.

Christopher Gardner: Nobody who?

[Christopher doesn't respond]

Christopher Gardner: Nobody who?

[Christopher still doesn't respond]

Christopher Gardner: A-ha-ha, that's a good one, I like that!

[repeated line]

Christopher Gardner: Christopher is staying with me.

Shoe-Spotting Intern: Hey, you're missing a shoe.

Christopher Gardner: Oh, hey, thanks!

Christopher Gardner: [voice-over] This part of my life... this part right here? This part is called "being stupid."

[after he hits Chris]

Driver Who Hits Chris: Hey, asshole! Are you all right, asshole?

[about Chris' bone-density scanner]

Homeless Guy #1: It's a time machine... I know it's a time machine...

Christopher Gardner: [voice-over] This machine in my lap? It is not a time machine.

[last narration lines]

Christopher Gardner: [voice-over] This part of my life... this part right here? This is called "happyness."

Christopher Gardner: This part of my life is called "internship."

Christopher: What are you doing?

Christopher Gardner: Paying a parking ticket.

Christopher: ...But we don't have a car anymore.

Christopher Gardner: Yeah, I know...

[last lines]

Christopher: Knock, knock.

Christopher Gardner: Who's there?

Christopher: Nobody.

Christopher Gardner: Nobody who?

[Christopher says nothing]

Christopher Gardner: Christopher, nobody who?

[Christopher says nothing]

Christopher Gardner: [laughs] Okay, that's funny.

Reverend Williams: The important thing about that freedom train, is it's got to climb mountains. We ALL have to climb mountains, you know. Mountains that go way up high, and mountains that go deep and low. Yes, we know what those mountains are here at Glide. We sing about them.

Pursuit of Happyness Summary

In 1981, in San Francisco, the smart salesman and family man Chris Gardner invested the family savings in Ostelo National bone-density scanners, an apparatus twice more expensive than x-ray with practically the same resolution. The white elephant financially breaks the family, bringing troubles to the relationship with his wife that leaves him and moves to New York. Without money and wife, but totally committed with his son Christopher, Chris sees the chance to fight for a stockbroker internship position at Dean Witter, disputing for one career in the end of six months training period without any salary with other twenty candidates. Meanwhile, homeless, he has all sorts of difficulties with his son.

Wednesday, June 24, 2009

Benjamin Button summary

On the day that Hurricane Katrina hits New Orleans, elderly Daisy Williams (nee Fuller) is on her deathbed in a New Orleans hospital. At her side is her adult daughter, Caroline. Daisy asks Caroline to read to her aloud the diary of Daisy's lifelong friend, Benjamin Button. Benjamin's diary recounts his entire extraordinary life, the primary unusual aspect of which was his aging backwards, being diagnosed with several aging diseases at birth and thus given little chance of survival, but who does survive and gets younger with time. Abandoned by his biological father, Thomas Button, after Benjamin's biological mother died in childbirth, Benjamin was raised by Queenie, a black woman and caregiver at a seniors home. Daisy's grandmother was a resident at that home, which is where she first met Benjamin. Although separated through the years, Daisy and Benjamin remain in contact throughout their lives, reconnecting in their forties when in age they finally match up. Some of the revelations in Benjamin's diary are difficult for Caroline to read, especially as it relates to the time past this reconnection between Benjamin and Daisy, when Daisy gets older and Benjamin grows younger into his childhood years.

Benjamin Button: Your life is defined by its opportunities... even the ones you miss.

Benjamin Button: It's a funny thing about comin' home. Looks the same, smells the same, feels the same. You'll realize what's changed is you.

Benjamin Button: I'm always lookin' out my own eyes.

Benjamin Button: I wanna remember us just as we are now.

Mr. Daws: Did I ever tell you I was struck by lightning seven times? Once when I was in the field, just tending to my cows:

[brief footage of a man getting struck by lightning]

Mr. Daws: Did I ever tell you I been struck by lightning seven times? Once when I was just sittin' in my truck just minding my own business:

[brief footage of a man getting struck by lightning]

Benjamin Button: Sometimes we're on a collision course, and we just don't know it. Whether it's by accident or by design, there's not a thing we can do about it. A woman in Paris was on her way to go shopping, but she had forgotten her coat - went back to get it. When she had gotten her coat, the phone had rung, so she'd stopped to answer it; talked for a couple of minutes. While the woman was on the phone, Daisy was rehearsing for a performance at the Paris Opera House. And while she was rehearsing, the woman, off the phone now, had gone outside to get a taxi. Now a taxi driver had dropped off a fare earlier and had stopped to get a cup of coffee. And all the while, Daisy was rehearsing. And this cab driver, who dropped off the earlier fare; who'd stopped to get the cup of coffee, had picked up the lady who was going to shopping, and had missed getting an earlier cab. The taxi had to stop for a man crossing the street, who had left for work five minutes later than he normally did, because he forgot to set off his alarm. While that man, late for work, was crossing the street, Daisy had finished rehearsing, and was taking a shower. And while Daisy was showering, the taxi was waiting outside a boutique for the woman to pick up a package, which hadn't been wrapped yet, because the girl who was supposed to wrap it had broken up with her boyfriend the night before, and forgot.

Benjamin Button: When the package was wrapped, the woman, who was back in the cab, was blocked by a delivery truck, all the while Daisy was getting dressed. The delivery truck pulled away and the taxi was able to move, while Daisy, the last to be dressed, waited for one of her friends, who had broken a shoelace. While the taxi was stopped, waiting for a traffic light, Daisy and her friend came out the back of the theater. And if only one thing had happened differently: if that shoelace hadn't broken; or that delivery truck had moved moments earlier; or that package had been wrapped and ready, because the girl hadn't broken up with her boyfriend; or that man had set his alarm and got up five minutes earlier; or that taxi driver hadn't stopped for a cup of coffee; or that woman had remembered her coat, and got into an earlier cab, Daisy and her friend would've crossed the street, and the taxi would've driven by. But life being what it is - a series of intersecting lives and incidents, out of anyone's control - that taxi did not go by, and that driver was momentarily distracted, and that taxi hit Daisy, and her leg was crushed.

Mr. Daws: Did you know that I was struck by lightning seven times?

Benjamin Button: [Voice over; letter to his daughter] For what it's worth: it's never too late or, in my case, too early to be whoever you want to be. There's no time limit, stop whenever you want. You can change or stay the same, there are no rules to this thing. We can make the best or the worst of it. I hope you make the best of it. And I hope you see things that startle you. I hope you feel things you never felt before. I hope you meet people with a different point of view. I hope you live a life you're proud of. If you find that you're not, I hope you have the strength to start all over again.

Mrs. Maple: Benjamin, we're meant to lose the people we love. How else would we know how important they are to us?

Captain Mike: You can be as mad as a mad dog at the way things went. You could swear, curse the fates, but when it comes to the end, you have to let go.

Queenie: You never know what's comin' for ya.

Benjamin Button: Our lives are defined by opportunities, even the ones we miss.

Queenie: Poor child, he got the worst of it. Come out white.

Mr. Daws: Did I ever tell you I been struck by lightning seven times? Once when I was repairing a leak on the roof.

[brief footage of a man getting struck by lightning]

Mr. Daws: Once I was just crossing the road to get the mail.

[brief footage of a man getting struck by lightning]

Mr. Daws: Once, I was walking my dog down the road.

[brief footage of a man getting struck by lightning]

Mr. Daws: Blinded in one eye; can't hardly hear. I get twitches and shakes out of nowhere; always losing my line of thought. But you know what? God keeps reminding me I'm lucky to be alive.

[sniffles]